This article first appeared in the newsletter of the Weathersfield (VT) Historical Society.

THE APRIL 8, 2024 SOLAR ECLIPSE

WHAT IS A SOLAR ECLIPSE?

A solar eclipse occurs when the Moon moves in front of the Sun from our point of view, blocking the light of the Sun and casting a shadow over a part of the surface of the Earth. If we are directly in that shadow, we experience a total eclipse. If we are nearby but not completely in the Moon’s shadow, we experience a partial eclipse.

There are two types of total eclipse, depending on the distance that the Moon is from the Earth when it passes in front of the Sun. The Moon’s orbit of the Earth is slightly elliptical, and thus at its closest, the Moon is 225,623 miles away, and at its furthest is 252,008 miles away. We notice this when we experience a “Super Moon” when the Moon is close to us and, particularly when it is at or near the horizon, looks much bigger than usual. A normal solar eclipse occurs when the Moon is near enough to us that it covers the entire disk of the Sun. If the Moon is more distant, it does not cover the entire surface of the Sun, and there is an outer band of the Sun’s perimeter still visible. This is called an annular eclipse. You probably won’t be surprised to learn that an annular eclipse is also known as a Ring of Fire.

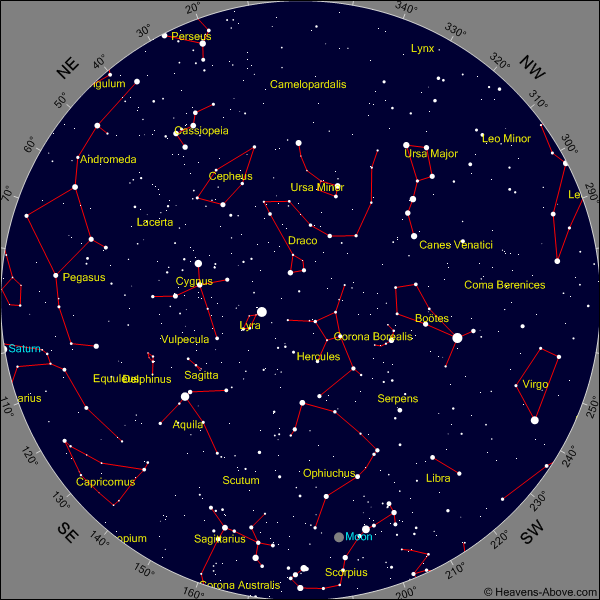

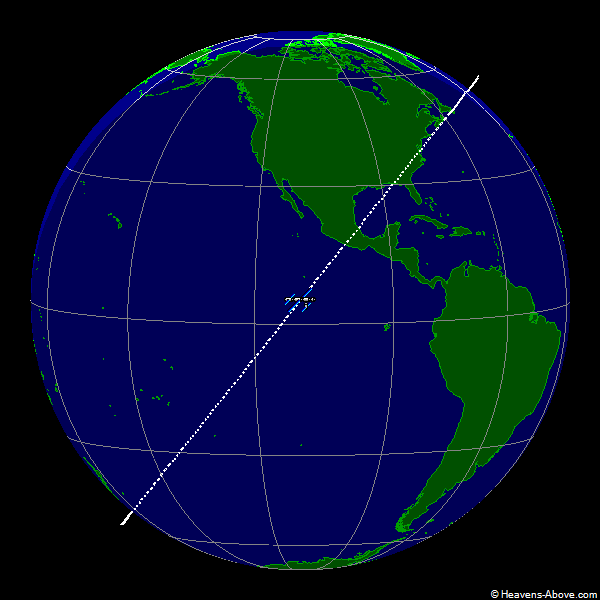

Total Eclipse, as will be visible in northern Vermont Partial Eclipse, as will be visible in Weathersfield.

Credit: Rick Fienberg / TravelQuest Int’l / Wilderness Travel Credit: Rick Fienberg / Sky & Telescope

ECLIPSES IN HISTORY

Although there is no historical record of any significant event in Weathersfield connected to solar eclipses, the 1932 annular eclipse did generate considerable media and scientific interest throughout Vermont. An article in the August 19, 1932 edition of the Vermont Phoenix discussed some of the questions posed by the scientific community: “It would be of great interest for physiologists to know whether the regular supply of milk and eggs was in any way upset by the eclipse. There are many cattle and chicken farms throughout the area where the eclipse is total and reports by farmers would be much appreciated by the society and would provide material for studies which may eventually prove helpful to the farmers themselves.”

Elsewhere there have been eclipses which are of historical interest. As early as 1302 BCE, Chinese observers recorded a total eclipse which blocked the Sun for nearly six an half minutes, and in 763 BCE a total eclipse darkened Assyria (now Iraq) for five minutes. Both of these events caused superstitious reactions; the eclipse in China was propitiated by the Emperor performing rituals and eating vegetarian meals; the Assyrian eclipse was mentioned in early records in connection with an insurrection in the city of Ashur.

Eclipses in 29 CE and in 33 CE in Jerusalem have been cited by various Christian historians as explaining the New Testament assertion that the sky darkened when Jesus was crucified. The 29 CE eclipse had a period of totality of just under two minutes, and the one in 33CE lasted just over four minutes.

The Koran mentions an eclipse preceding the birth of Mohammed, and some religious historians point to a three minute and 17 second total eclipse in 569 CE as signaling that event. And on January 27, 632 CE, the day when Mohammed’s 18 month old son Ibrahim died, a partial eclipse occurred. Muhammed himself, however, is said to have stated that the Sun does not eclipse to signal human events.

The son of William the Conqueror, King Henry the First of England died in 1133 CE, and on that day there was a total eclipse which lasted slightly over four and a half minutes. Historian William of Malmesbury (1080-1143) wrote of the event that “hideous darkness agitated the hearts of men.”

Setting aside these attempts of non-scientific ancients to make human sense of the movements of the cosmos, the 1919 eclipse is of historical and scientific importance. Four years earlier, Albert Einstein had published his Theory of General Relativity, which was received with some skepticism by much of the scientific community. One of its assertions was that the gravity of massive objects like the Sun curves space time in their vicinity, and this curvature must affect the trajectory of light as it passes near.

An eclipse, by darkening the daytime sky, would allow for observation and photography of stars in the area surrounding the Sun. By then observing and photographing the same stars in the night sky, any effect of the Sun on the apparent position of the stars could be observed and measured. Expeditions sponsored jointly by the Greenwich and Cambridge Observatories were mounted to Sobral, Brazil and to the island of Principe off the coast of Africa, and when the results of the observing and photography were studied and analyzed, Einstein’s predicted degree of curvature of the path of light was confirmed and he became an overnight celebrity.

HOW TO OBSERVE THE UPCOMING ECLIPSE

Even at 90% obscured, the Sun will not be safe to look at it directly, and ordinary sunglasses do not provide nearly enough protection.

With eclipse glasses, which are inexpensive and available from a variety of online sources, you will be able to observe the Sun directly during the entire two and half hours that it will take for the Moon to pass in front of the Sun. Get the ones with black polymer lenses; glasses made from mylar are not recommended, as they can be scratched and even a tiny pinhole can allow a dangerous amount of light through.

Welding glasses of shade #14 are safe. Anything less than #14 is not safe.

You should hold your glasses up to a bright light source and check them for any light leakage. If they are compromised, do not use them. Cut them up and put them in the trash.

One trick which some observers use when they are experiencing a total eclipse is to wear an eyepatch over their dominant eye for twenty minutes or so before totality, so that when the Sun is hidden and the stars emerge, they will be light-adapted and able to see more of the stars in the sky.

The safest way to observe an eclipse is by indirect viewing, which is both easy and fun.

With a thumbtack poke a hole in the center of a piece of paper or cardboard, and hold another sheet of cardboard or paper below it. Position the papers so that sunlight passes through the hole and onto the lower surface. And if you poke two holes, you can project two images. Or get a colander and project dozens of images at a time. You can also stand under a tree and look down at hundreds of images of the eclipse on the ground as light passes through the spaces between the tree’s leaves.

WHERE TO OBSERVE THE UPCOMING ECLIPSE

The April 8th eclipse will be the last eclipse in the United States until 2045. So, it’s worth thinking about whether or not you should travel a couple hours to see the eclipse in its totality. Those who have experienced a total eclipse often use terms like “awe-inspiring” and “life-changing” to describe those two or three minutes in which day will become night, birds will fall silent, and the stars will come out.

If you do opt for the total eclipse, consider that you will not be the only car on the road. In fact, it might be wise to think of the eclipse as being like foliage season, if the colors only lasted for a couple hours and only occurred in two or three counties.

Once you decide to head north, there are hundreds, perhaps thousands, of good viewing sites. A ball field, a parking lot, the green in a small town, any public open space will do; just make sure there will be no light pollution during the minutes of darkness.

If you decide to stay here, where we will see a 92 or 93% eclipse, viewing should be very easy. Most of us can probably find a place on our own deck or front lawn which will work fine. All that is needed is a clear view to the south and west.

If you want to experience the eclipse with friends and neighbors, you are invited to come to Hoisington Field. We have reserved the field from 1 to 5 pm, but the actual eclipse will begin at about 2:15, and will end a little after 4:30. This is a joint event of The Weathersfield Proctor Library, the Reading Public Library, and the Southern Vermont Astronomy Group (SoVerA). There will be at least two telescopes equipped with solar filters for safe viewing, and there will be a limited number of free solar viewing glasses available. As I write, a new solar telescope is on its way to Weathersfield. This is the result of a nearly $5,000 grant awarded by the American Astronomical Society. For the technically inclined, the scope is a Coronado 70 SolarMax III Solar Telescope with a SolarQuest tripod and motorized alt-azimuth mount. The filter is an H-alpha filter, which will allow for clear views of the granular surface of the Sun including sunspots, and also the solar prominences which radiate visibly outward at the perimeter of the Sun’s disk.

Here’s a fun fact: despite being 93 million miles away, the Sun is so large that the distance from us to the closest part of the equator of the Sun is so much greater than the distance from us to the outer edges of the sun, that we have to change the focus of our viewing telescopes when we go from the center to the edge of the Sun.

And wherever you choose to view the eclipse, bring a folding chair and remember to dress warmly, including your warmest boots. Staying outdoors in April is a cold business, and you will want to be able to enjoy yourself while you do it.

Roderick Bates is a member of the Weathersfield Historical Society, a Trustee of the Weathersfield Proctor Library, and a member of the Board of Directors of the Southern Vermont Astronomy Group. He lives with his wife Lynda Tallarico on Chimney Ridge, where he edits the poetry journal Rat’s Ass Review.

Sources:

Burlington Free Press: “A look back at Vermont’s solar eclipse history, and a look ahead to the next total eclipse” by Ella Ruehsen June 11, 2021

Space.com: “The 7 Most Famous Solar Eclipses in History” by Tia Ghose, November 13, 2012

Brittanica.com: “9 Celestial Omens” by Erik Gregersen

Airandspace.si.edu: “The Death of a King, End to a War, and the Solar Eclipse” May 12, 2017, by Zachary Hullings, The Smithsonian Institute

The Royal Society Journal of the History of Science: “The 1919 eclipse results that verified general relativity and their later detractors: a story re-told” by Gerard Gilmore and Gudrun Tausch-Pebody, October 21, 2021