So here we are, after December 21, 2012, still in existence. This takes most of the urgency out of our collective curiosity about the Mayan Calendar. However, for those who still have a lingering interest, this article may shed some light.

Our Main Source: The Dresden Codex

The Maya civilization extended from 1800 BCE until the arrival of the Spanish, and was at its height between the 3rd and 9th Centuries.

Most of what we know of the Mayan calendar system comes from the Dresden Codex, a Mayan text which, among other things, records the movements of the moon and of Venus. The existing text is from the 11th or 12th Century, but is believed to be a copy of an original 300 or 400 years older.

The Dresden Codex is considered the most complete of the three undisputedly authentic Mayan codices. It is called the Dresden Codex because it is housed in the Royal Library in Dresden.

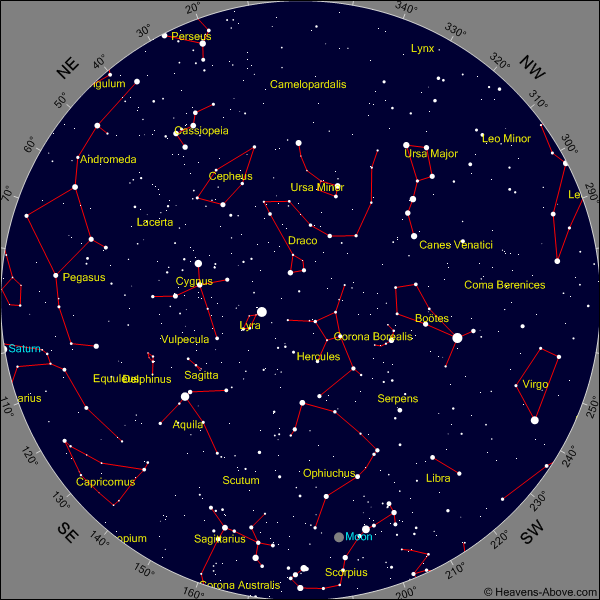

The Dresden Codex contains astronomical tables of outstanding accuracy. It is most famous for its Lunar Series and Venus Table. The lunar Series has intervals correlating with eclipses. The Venus Table correlates with the apparent movements of the planet. The codex also contains almanacs, astronomical and astrological tables, and ritual schedules. The Dresden Codex contains predictions for agriculturally-favorable timing. It has information on rainy seasons, floods, illness and medicine. It also seems to show conjunctions of constellations, planets and the moon.

The Mayan Calendar

The Mayan Calendar has as its base the Uinal, a 20 day month. 18 Uinals, totaling 360 days, were followed by a 5 day period of “nameless days.” The nameless days were believed to be unlucky; people tended to stay inside. This interval of 18 Uinals and five nameless days, which was one Solar Year, was called a Tun. It began and ended with the Winter Solstice.

The Long Count

As we in our tradition count months, years, decades, centuries and millennia, the Maya had a system of counting larger spans of time. They did not use a simple decimal system like ours; they based their count on intervals of 20 (with the exception of the 18 Uinals needed to make a solar year).

Here are the basics of the Mayan system of counting years:

20 days = 1 Uinal

18 Uinal = 1 Tun (one solar year)

20 Tun = 1 Ka’tun (19.7 solar years)

20 Ka’tun = 1 Bak’tun (394 yrs)

20 Bak’tun = 1 Pictun (7,885 yrs)

20 Pictun = 1 Kalabtun (157,808 yrs)

20 Kalabtun = 1 K’inchiltun (3,156,164 yrs)

20 K’inchiltun = 1 Alautun (63,123,288 yrs)

So What Was All This About he World Ending?

According to Maya belief, the world began on September 6, 3114 BCE. Thus December 21, 2012, which is 1,872,000 days from the Mayan creation date, is the final day of the 13th Bak’tun. This event is similar to our observing the end of a Century. There are another 7 Bak’tun to go before we hit an anniversary that by the Mayan way of thinking hasn’t come and gone many times already: in another 2758 years the 20th Bak’tun will end, concluding the first Pictun.

However, according to the Maya, there are three larger counts still to go after the Pictun, and it will not be until some 63 million plus years from now that the Mayan calendar will have reached its conclusion. Whether it will then repeat is something that we do not yet know. However, there is nothing in the Mayan scheme of counting that would indicate that this December 21 is anything but the end/beginning of another typical cycle of years.

According to the Maya, on December 21, 2012 the Tun ended with five nameless days, during which any remaining Maya presumably hunkered down indoors, and then at the end of the Tun, all came out and celebrated a big New Year’s Day which began not just another Tun, but a new Ka’tun (the 280th), and a new Baktun (the 14th).

So, from the Maya to you, Happy New Year!